[This essay is an adaptation of my talk at Active Ingredients Conference]

It's never been better for programmers, a team of 5 today can build projects and companies that required hundreds if not thousands of engineers just a few decades ago. So although Fred Brooks was right in that there was "no silver bullet" which "by itself promises even an order of magnitude improvement in productivity" I'd argue that there was a million silver arrows that collectively got us those improvements.

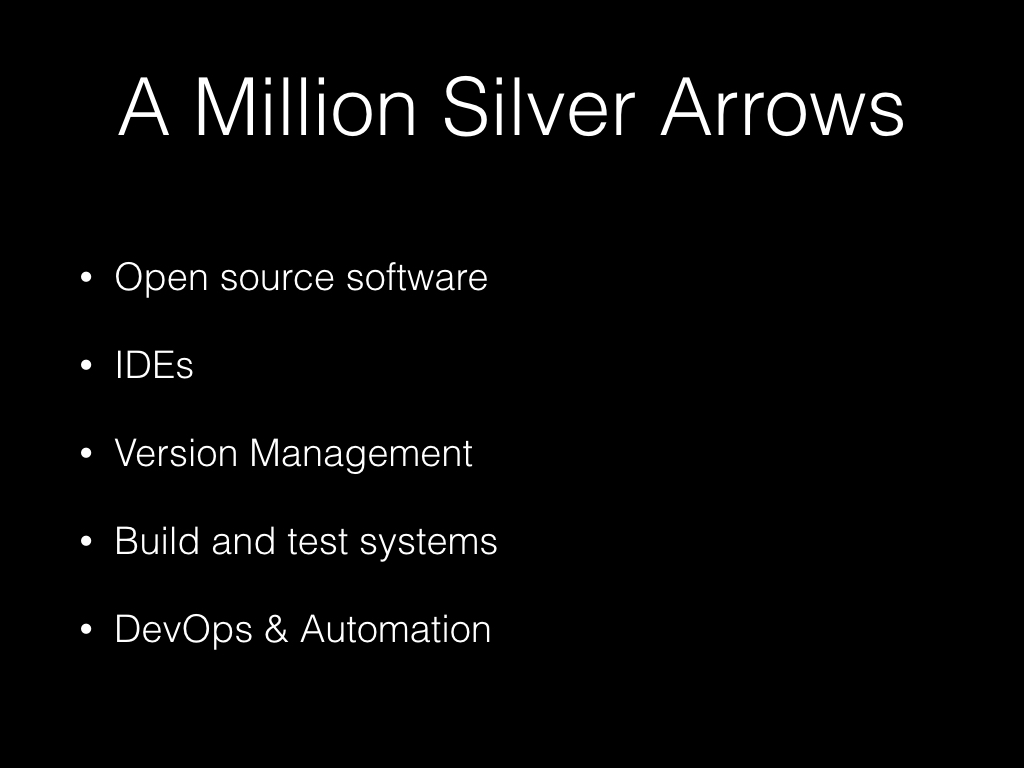

Much of this came through open source software, development tools and open source development tools.

However, this happened as a wave of distributed innovation. There was no central planning and no vision — it all happened organically. Which explains why a lot of our day-to-day development tools overlap, compete, and require a ton of compatibility code just to make them work with each other.

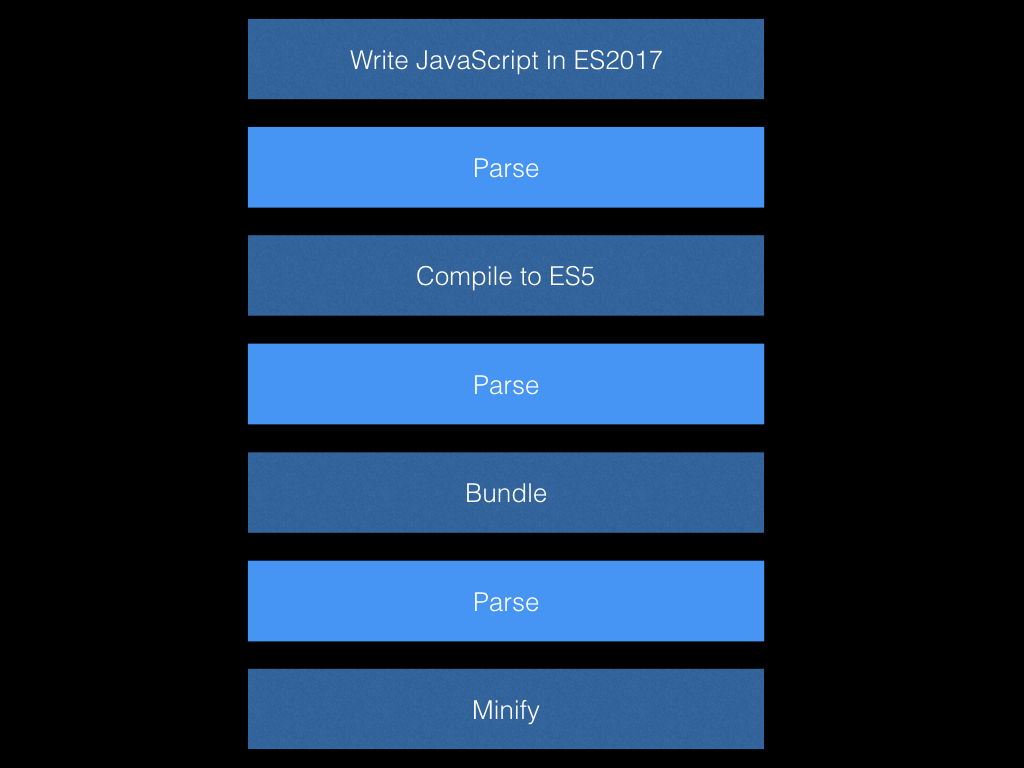

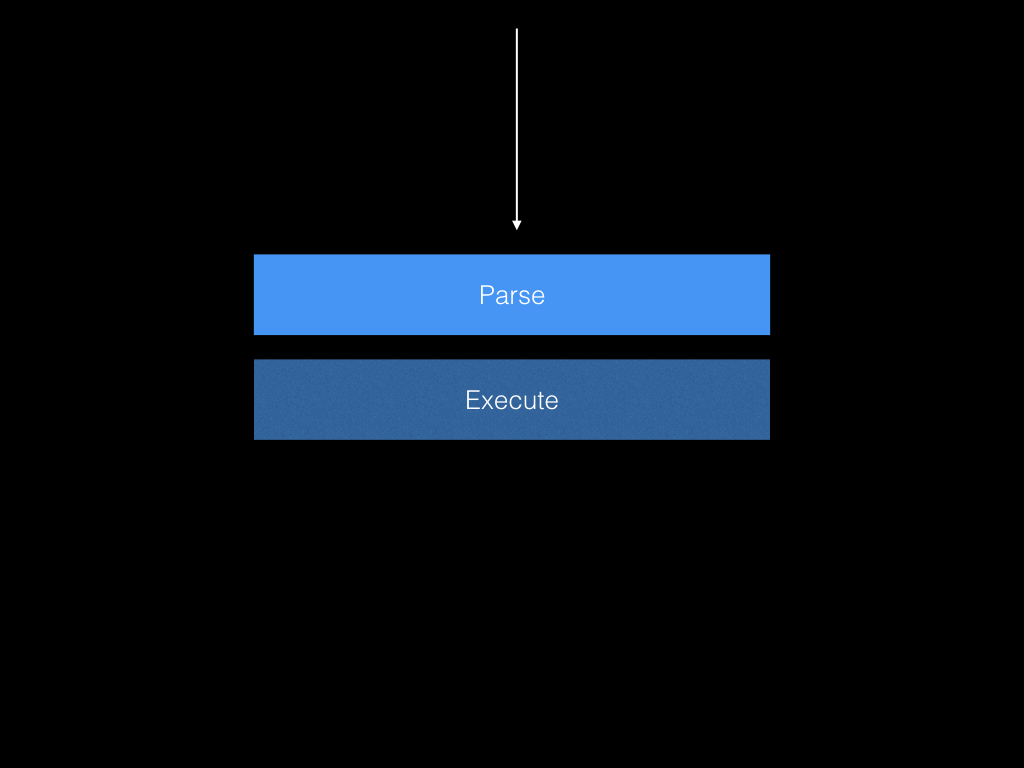

Let's take an example. Say you're a JavaScript developer and you use the latest and greatest tools. You write your code in ES2017. But before you ship it to your users you use a compiler like Babel which has to parse your code to compile it to ES5. And you also want to bundle your code so you use a bundler like Webpack which parses your ES5 code, collect the require/import statements, and bundles your code. Finally, you also use a minifer like Uglify which has to also parse and then minify your code.

You may have noticed that there is only 3 parse steps in this pipeline, that's because I ran out of slide space. The browser still needs to parse the code before it executes it.

Ok, so what? Well, there is a good chance you're reading this article to kill time while Webpack is recompiling. Everything is slow. There is also a question of how many parsers, as a community, do we have to write and maintain. Furthermore, there is lot of information loss as we go down the pipeline — you might've had Flow type annotations but those will not be accessible for the minifier to emit optimized code because they're compiled away at an earlier step.

(This is only one branch of the development pipeline, there is also the IDE/static analysis and code generation that contains similar duplication of work and incompatibilities).

Roughly speaking, we separate our tools by development life-cycle stage: authoring, executing, testing, building, and deployment. Which limits how much sharing of information and work can happen between tools.

Ok, then what if we imagined we live in a different world where we've taken a more holistic approach to development environments where we layer tools on top of each other. My IDE knows where and how my code executes and can show me inline information about function calls, error rates, and type information — heck, why won't production crashes translate into local development breakpoints? What if my repo on Github could pull from the same code intelligence service and have a click-to-symbol feature. Etc.

Alan Kay tells us that computing is "pop culture" because we have "disdain for history". Well, I'd like to do better. So in looking at this problem I decided to construct a historical narrative to help us understand how we got here.

Worse Is Better

In March 1990 Gaberial stood in front of crowd of Lisp developers and told them that "Worse is Better". The Lisp community's who's who were in the audience and they weren't very happy with the talk. After the talk, Gerry Sussman was the first to stand up and claim nonsense. Followed by Carl Hewitt, and there was Gaberial defending a position that, had the Lisp community understood, maybe the world of software engineering today would've been very different.

See the Lisp community practiced the Right Thing software philosophy which was also know as "The MIT Approach" and they were also known as "LISP Hackers".

The larger research community that the Lisp community was part of was operating under a vision of computing that Alan Kay recently mentioned in a Quora answer: “The destiny of computers is to become interactive intellectual amplifiers for everyone in the world pervasively networked worldwide”.

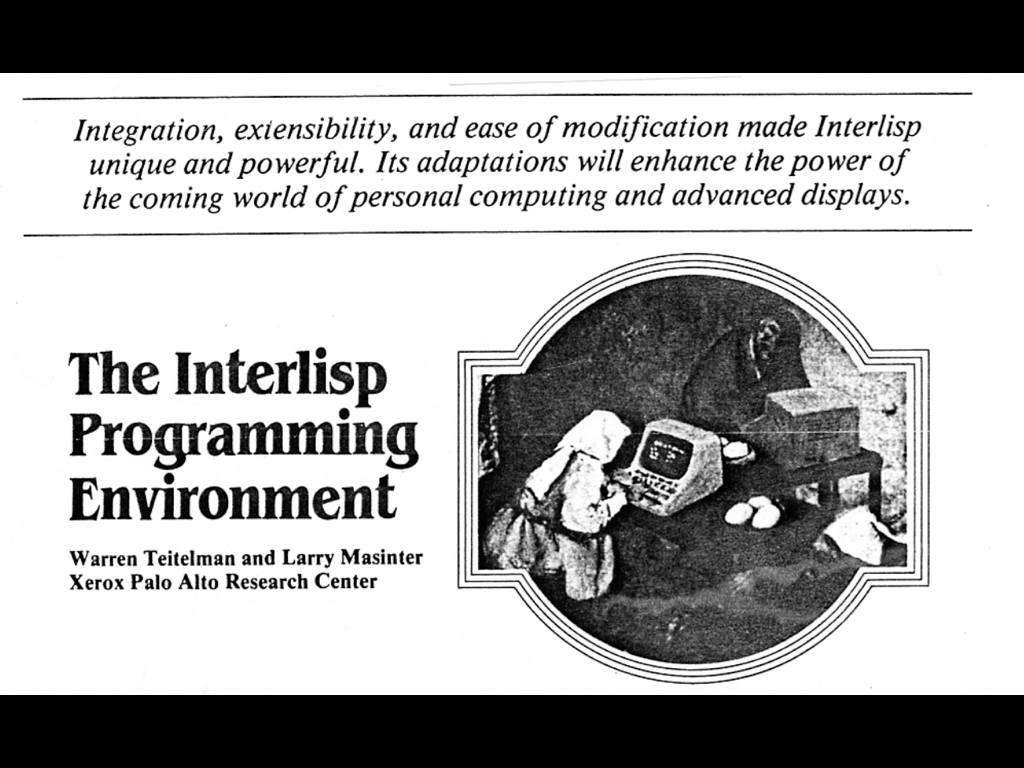

They were building amazing technology. Take for example Interlisp, a bootstrapped end-to-end Lisp programming environment that featured a structure editor (picture editing AST nodes instead of text), a REPL (with undo, which right now is coming back as "time-traveling debugger") and among many other things automatic error correction.

Meanwhile in New Jersey the "Worse is Better" folks, also known as "New Jersey Style", also known as "C hackers" were hacking on the C programming language and the Unix operating system. They had a much more pragmatic approach than the MIT approach — they valued, above anything else, a simplicity of implementation. Almost exactly the opposite of what the MIT folks valued, which is simplicity of interface, completeness, and correctness.

(I like to imagine a late-night stoner-like conversation between Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson:

"Dude, what if, like, everything was made of files?"

"Everything?"

"Yeah, like eeverrryyything"

"Whoaa")

Back to Richard Gabriel. After he was lambasted by everyone at the conference he went home, hid his essay, and vowed never to talk about it again. See he knew that in the wrong hands Worse is Better — which although the New Jersey folks were practicing they weren't preaching — could do a lot of damage.

A couple of years later Richard hired a young hacker by the name of Jamie Zawinski (later of Netscape fame — and can be found running a nightclub somewhere in the SoMa district of SF). Like most hackers Jamie believed that information should be free so when he found the Worse is Better paper he decided, without asking Richard, to send it to all his friend. It then spread like wildfire across the industry.

What was supposed to be a wake up call became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Richard talks about how "Large companies (with 3-letter names)" (hint: IBM) used the Worse is Better paper a reference for training employees on how to design software.

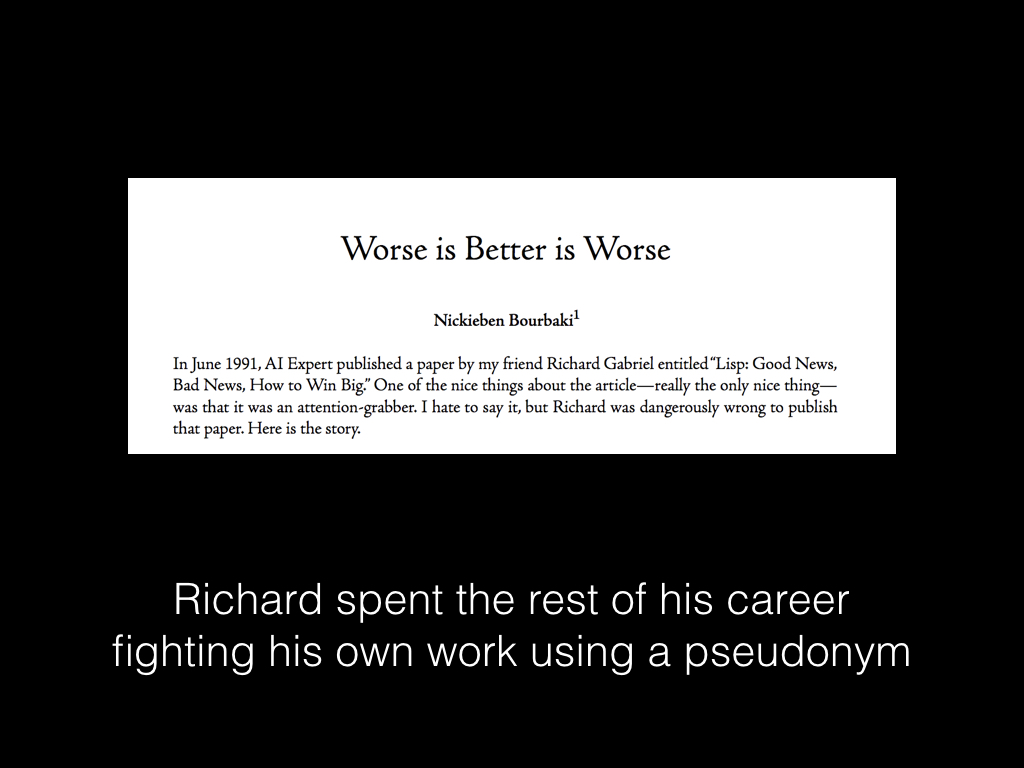

Later in his career Richard — realizing that he was responsible for the final nail in the coffin that killed the Right Thing approach to software development — began writing against Worse is Better under a pseudonym. Legend has it that he became so confused about this subject that he was once invited to talk about it and both argued for and against Worse is Better.

Now that I understand our place in history I can't help but wonder what would've happened if the Right Thing philosophy had won out. If our development environment resembled something like Interlisp instead of Unix. I think maybe since the main feature of Worse is Better is that — in the words of Richard — "it spreads like virus" it had been better for computing to adopt this approach to achieve scale. But now what? I think we should be more ambitious and bring back the Right Thing.

(In the talk which this is based on I talk a bit about what I'm doing about the problem. I've written briefly about this elsewhere: "Building Towards a Holistic Development Service")